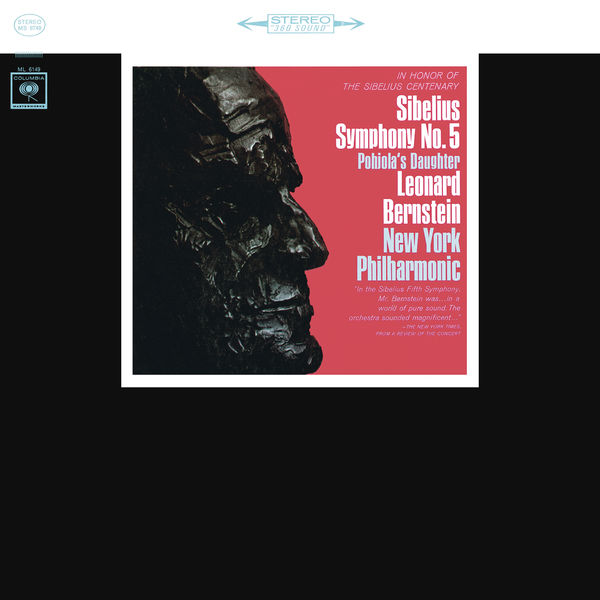

New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Leonard Bernstein – Sibelius: Symphony No. 5 in E-Flat Major, Op. 82 & Pohjola’s Daughter, Op. 49 (1965/2015)

FLAC (tracks) 24 bit/44,1 kHz | Time – 45:27 minutes | 452 MB | Genre: Classical

Studio Masters, Official Digital Download | Front Cover | © Sony Classical

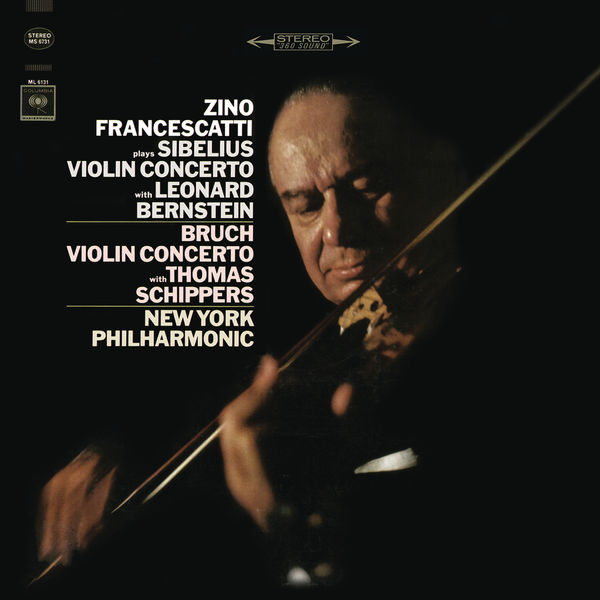

Zino Francescatti, New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Thomas Schippers, Leonard Bernstein – Sibelius: Concerto in D Minor for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 47 / Bruch: Concerto No. 1 in G Minor for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 26 (1965/2015)

FLAC (tracks) 24 bit/44,1 kHz | Time – 50:43 minutes | 501 MB | Genre: Classical

Studio Masters, Official Digital Download | Front Cover | © Sony Classical

Bernstein – Remastered Edition: Sibelius – The Symphonies collects Bernstein’s complete Sibelius recordings, newly remastered from the original analogue tapes using 24 bit / 96 kHz technology in a 7CD limited original jackets collection.

Bernstein regarded Sibelius alongside Mahler as one of “the key turning points” in the development of the 20th century symphony, though his reputation as a Mahler exponent has overshadowed a lifelong dedication to the Finnish composer. His advocacy goes back to the time of his association with Koussevitzky, with whom he studied at Tanglewood in 1940, later becoming his assistant. At Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute in 1941, he conducted the Second Symphony. And following his sensational New York Philharmonic debut in November 1943, one of Bernstein’s first engagements was a Montreal Symphony Orchestra concert in March 1944 that included his first performance of the First.

The Finnish composer’s centenary year, 1965, brought a flurry of activity. In New York, Bernstein conducted all the symphonies in a single season (only his mentor Serge Koussevitzky had done that in the US, three decades earlier in Boston). For his efforts, Bernstein was made a Commander of the Order of the Lion by the president of Finland. By this time, he was already well into his recorded Sibelius cycle, begun in February 1961 with the Fifth Symphony, completed in May 1967 with the Sixth.

Bernstein’s Sibelius, like his teacher’s, was “warm like the sun” rather than a more orthodox evocation of cold northern soundscapes. He once called Sibelius “a great and strange kind of genius”, but in his New York cycle he favors visceral excitement over strange remoteness.

This set also contains his recording of Sibelius’s Violin Concerto with the French virtuoso Zino Francescatti. Also included are Valse triste, The Swan of Tuonela, a rather brash Finlandia, a thrilling performance of Pohjola’s Daughter and Luonnotar – Sibelius’s haunting setting of words from the Kalevala, the Finnish national epic (with American soprano Phyllis Curtin) – as well as Bernstein’s only recording of Grieg’s Peer Gynt Suites. But it’s the Sibelius symphonies that are the chief attraction here, and this often stunningly well-played, first completed stereo cycle has lost none of its freshness and authority in the half century since it was recorded.

Read more

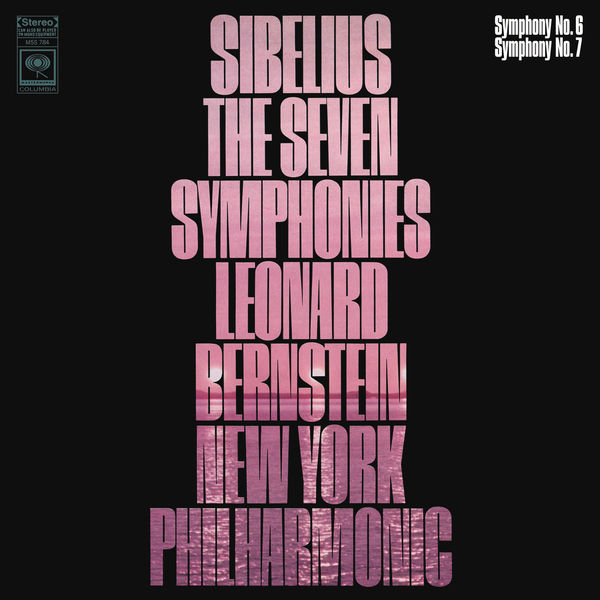

New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Leonard Bernstein – Sibelius: Symphonies Nos. 6 & 7 (1968/2015)

FLAC (tracks) 24 bit/44,1 kHz | Time – 49:28 minutes | 494 MB | Genre: Classical

Studio Masters, Official Digital Download | Front Cover | © Sony Classical

Bernstein – Remastered Edition: Sibelius – The Symphonies collects Bernstein’s complete Sibelius recordings, newly remastered from the original analogue tapes using 24 bit / 96 kHz technology in a 7CD limited original jackets collection.

Bernstein regarded Sibelius alongside Mahler as one of “the key turning points” in the development of the 20th century symphony, though his reputation as a Mahler exponent has overshadowed a lifelong dedication to the Finnish composer. His advocacy goes back to the time of his association with Koussevitzky, with whom he studied at Tanglewood in 1940, later becoming his assistant. At Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute in 1941, he conducted the Second Symphony. And following his sensational New York Philharmonic debut in November 1943, one of Bernstein’s first engagements was a Montreal Symphony Orchestra concert in March 1944 that included his first performance of the First.

The Finnish composer’s centenary year, 1965, brought a flurry of activity. In New York, Bernstein conducted all the symphonies in a single season (only his mentor Serge Koussevitzky had done that in the US, three decades earlier in Boston). For his efforts, Bernstein was made a Commander of the Order of the Lion by the president of Finland. By this time, he was already well into his recorded Sibelius cycle, begun in February 1961 with the Fifth Symphony, completed in May 1967 with the Sixth.

Bernstein’s Sibelius, like his teacher’s, was “warm like the sun” rather than a more orthodox evocation of cold northern soundscapes. He once called Sibelius “a great and strange kind of genius”, but in his New York cycle he favors visceral excitement over strange remoteness.

This set also contains his recording of Sibelius’s Violin Concerto with the French virtuoso Zino Francescatti. Also included are Valse triste, The Swan of Tuonela, a rather brash Finlandia, a thrilling performance of Pohjola’s Daughter and Luonnotar – Sibelius’s haunting setting of words from the Kalevala, the Finnish national epic (with American soprano Phyllis Curtin) – as well as Bernstein’s only recording of Grieg’s Peer Gynt Suites. But it’s the Sibelius symphonies that are the chief attraction here, and this often stunningly well-played, first completed stereo cycle has lost none of its freshness and authority in the half century since it was recorded.

Read more

New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Alan Gilbert – Nielsen: Symphonies Nos. 5 & 6 (2015)

FLAC (tracks) 24 bit/88,2 kHz | Time – 01:11:25 minutes | 1,10 GB | Genre: Classical

Studio Masters, Official Digital Download | Front Cover | © Dacapo

Nielsen was a high energy composer, perfectly suited to a “muscle” orchestra like the New York Philharmonic. Listening to these two performance we are reminded how the world of classical recordings has been taken over by orchestras of the second rank–professionally adequate, ambitious, able to fund their own recording programs and often to get released on major labels, but singularly lacking in the sort of corporate virtuosity and ensemble balances at all dynamic levels so tellingly in evidence here. If you like your Nielsen big, bold, and gutsy, then this is the cycle you need to own.

This doesn’t mean that Gilbert and his players are in any way crude. The opening of the Fifth Symphony emerges with gossamer delicacy, and the solo wind playing is as sensitive as one could wish. But the hostile snare drum entrance carries real menace, while the movement’s adagio second half, beautifully spun out by the strings, features the best percussion cadenza since Horenstein, leading to an absolutely apocalyptic climax. Similarly, Gilbert brings thrilling energy to the start of the second movement. The ensuing quick fugue isn’t as swift as some, but the orchestra’s weight of tone, its attention to detail, makes the music unusually vicious, while the race to the closing bars has seldom sounded more exhilarating.

The Sixth Symphony can come off as sort of a bitter, denatured coda to the previous five. Again, without minimizing the work’s etherial moments and often stark instrumental textures, Gilbert and the orchestral put the meat back on the music’s bony skeleton. The climax of the first movement is really terrifying, the Humoresque vividly grotesque. In the Adagio “Proposta seria,” the strings dig into their parts with painful intensity, leaving a finale in which Gilbert ensures that each variation has its own vivid character. The wacky waltz, even in it’s ghostly early stages, seethes with a latent energy that makes sense of the violent eruptions from the brass and bass drum that rip it apart shortly afterwards.

One textural note: these performances seem not to be using the latest Critical Edition of the symphonies–you can tell from the fact that the loud timpani triplets are still present towards the end of the finale’s opening section, to cite one example. This is not a wrong decision; the Critical Edition took an excessively dogmatic view in its efforts to present Nielsen’s first thoughts, eliminating revisions based on the practical realities of performance, even if these were accepted–whether tacitly or explicitly–by the composer. Nielsen was never faced with a situation like Bruckner’s, in which a crew of well-meaning but misguided supporters altered and manifestly falsified the basic text. Additions and modification to his scores were limited mostly to small but sometimes telling details, such as the additional timpani part just mentioned.

The excellent live sonics add to the tactile immediacy of the performances. If the foregoing sounds as though this team saved their best for last, well, I would say that they did. One quibble though: the booklet notes, by Jens Cornelius, are surprisingly poor. He seems to think that the snare drummer in the Fifth Symphony is a timpanist, and his language is both pretentious and stilted. Normally I wouldn’t care or mention it, save for the fact that it seems so odd and uncharacteristic. Never mind, it’s the music that matters, and about that there can be no question whatsoever. This is fantastic. –David Hurwitz, Classics Today

Read more

New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Alan Gilbert – Nielsen: Symphonies Nos. 1 & 4 (2014)

FLAC (tracks) 24 bit/88,2 kHz | Time – 01:09:20 minutes | 1,10 GB | Genre: Classical

Studio Masters, Official Digital Download | Front Cover | © Dacapo

These are strong, exciting performances of symphonies that demand the sort of bold muscularity in their execution that these artists offer. In Alan Gilbert’s hands the First Symphony sounds extremely confident and wholly mature. It starts with a bang and the tension in the first movement never lets up. The playing of the New York Philharmonic throughout is fresh and unaffected, full of spirit and drive. Even the Andante flows purposefully forward, and contrasts nicely with the Allegro comodo that does duty for a scherzo–with its harmonic kinks so personal to Nielsen. The finale has the same “pedal to the metal” drive as the opening, bringing the performance to a rousing conclusion.

The performance of the “Inextinguishable” Fourth Symphony also features some really impressive energy and power. In the first movement the brass play with a precision and clarity that few other versions can match, and in the finale the dueling timpani compete with real bravura. The slow movement here reminds me of Shostakovich in its bleak intensity, and my only quibble with Gilbert’s interpretation concerns the symphony’s coda where, like most of his colleagues, Gilbert broadens the pace in the closing bars when Nielsen clearly wants to drive the music home in tempo. Gilbert does pull it off: with an orchestra that has the weight and strength of the New York Philharmonic the effect is convincing, but Gibson (on Chandos) remains unmatched here.

Dacapo’s engineering, as with the previous release in this series, is natural and very present. The woodwinds feel just slightly recessed in more fully scored sections, but I can attest that the music really does sound like this in actual performance with a large orchestra, and certainly nothing gets lost. More importantly, the engineers have captured the impression of a live performance, caught on the wing, and the audience is mercifully quiet. This is a very impressive release. –David Hurwitz, Classics Today

New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Leonard Bernstein – Grieg: Peer Gynt Suite No. 1 & No. 2 / Sibelius: Finlandia & Valse Triste & The Swan of Tuonela (1981/2015)

FLAC (tracks) 24 bit/44,1 kHz | Time – 54:47 minutes | 529 MB | Genre: Classical

Studio Masters, Official Digital Download | Front Cover | © Sony Classical

Bernstein – Remastered Edition: Sibelius – The Symphonies collects Bernstein’s complete Sibelius recordings, newly remastered from the original analogue tapes using 24 bit / 96 kHz technology in a 7CD limited original jackets collection.

Read more![New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Leonard Bernstein - Bernstein: Symphonic Dances from 'West Side Story' & Symphonic Suite from 'On The Waterfront' (1961/2017) [Official Digital Download 24bit/192kHz] Download](https://imghd.xyz/images/2022/09/02/0886446017174_600.jpg)

New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Leonard Bernstein – Bernstein: Symphonic Dances from ‘West Side Story’ & Symphonic Suite from ‘On The Waterfront’ (1961/2017)

FLAC (tracks) 24 bit/192 kHz | Time – 40:31 minutes | 1,35 GB | Genre: Classical

Studio Masters, Official Digital Download | Front Cover | © Sony Classical

![New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Leonard Bernstein, Marin Alsop - Bernstein: Symphony No. 3 'Kaddish' (To the Beloved Memory of John F. Kennedy) (1963/2017) [Official Digital Download 24bit/192kHz] Download](https://imghd.xyz/images/2022/09/02/0636943974223_600.jpg)

New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Leonard Bernstein, Marin Alsop – Bernstein: Symphony No. 3 ‘Kaddish’ (To the Beloved Memory of John F. Kennedy) (1963/2017)

FLAC (tracks) 24 bit/192 kHz | Time – 42:53 minutes | 1,31 GB | Genre: Classical

Studio Masters, Official Digital Download | Front Cover | © Naxos

![New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Leonard Bernstein - Bernstein: Chichester Psalms for Chorus and Orchestra & Facsimile (1965/2017) [Official Digital Download 24bit/192kHz] Download](https://imghd.xyz/images/2022/09/02/0886446017280_600.jpg)

New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Leonard Bernstein – Bernstein: Chichester Psalms for Chorus and Orchestra & Facsimile (1965/2017)

FLAC (tracks) 24 bit/192 kHz | Time – 37:11 minutes | 1,12 GB | Genre: Classical

Studio Masters, Official Digital Download | Front Cover | © Sony Classical

![Philippe Entremont, Zino Francescatti, New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Leonard Bernstein - Bernstein: The Age of Anxiety & Serenade after Plato's 'Symposium' (1966/2017) [Official Digital Download 24bit/192kHz] Download](https://imghd.xyz/images/2022/09/02/0886446017303_600.jpg)

Philippe Entremont, Zino Francescatti, New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Leonard Bernstein – Bernstein: The Age of Anxiety & Serenade after Plato’s ‘Symposium’ (1966/2017)

FLAC (tracks) 24 bit/192 kHz | Time – 01:07:21 minutes | 2,64 GB | Genre: Classical

Studio Masters, Official Digital Download | Front Cover | © Columbia Records

Symphony No. 2, “The Age of Anxiety” :: Anyone who grew up in America in the late 1950s probably first encountered classical music through a series of Young People’s Concerts, presented on television by Leonard Bernstein. Bernstein’s gently narrated, eloquent descriptions examined many aspects of his art.

One program explained that music, in itself, is never “about” anything but music. For his example, Bernstein chose the tone poem Don Quixote by Richard Strauss, specifically Variation 2, in which the Don meets a flock of sheep on the road and believes them to be soldiers. Before playing the episode, however, Bernstein created a fanciful story about a group of motorcycle riders, and allowed the music graphically to illustrate a completely different idea. His point was made.

In 1947, W. H. Auden published an epic poem, The Age of Anxiety, concerned with 20th-century man’s search for God. The poem won a Pulitzer Prize, and Bernstein, deeply moved, chose it as the subject matter for a symphony. He added a solo piano part, representing himself as a spectator. The story concerns four disenchanted people searching for faith, and Bernstein composed music to illustrate the descriptions on the printed page. At the end, after a jazz interlude for piano and percussion, “the characters disperse,” and an Epilogue, for orchestra alone, represents faith itself. Later, Bernstein rewrote the finale, adding a cadenza before the coda to round out the work’s concert function. In other words, he followed his own maxim about music not being related to anything except itself. The music had acquired a life—and a separate personality—of its own, despite the words that inspired it. —Paul Myers

(more…)

![Glenn Gould, New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Leonard Bernstein - Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 4 in G Major, Op. 58 (1961/2015) [Official Digital Download 24bit/44,1kHz] Download](https://imghd.xyz/images/2022/08/25/0886445060386_600.jpg)

Glenn Gould, New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Leonard Bernstein – Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 4 in G Major, Op. 58 (1961/2015)

FLAC (tracks) 24 bit/44,1 kHz | Time – 36:50 minutes | 365 MB | Genre: Classical

Studio Masters, Official Digital Download | Digital Booklet, Front Cover | © Sony Classical

This was the concerto with which Gould gave his orchestral début, playing its first movement on 8 May 1946. “Who does the kid think he is, Artur Schnabel?” snorted one critic, while another touted the thirteen-year-old boy as a “genius.” Whatever the case, this was the Beethoven concerto he played most frequently in public—twenty-nine times.

(more…)