![Itzhak Perlman, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Carlo Maria Giulini - Brahms: Violin Concerto (2015) [Official Digital Download 24bit/96kHz] Download](https://imghd.xyz/images/2022/09/10/0825646073818_600.jpg)

Itzhak Perlman, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Carlo Maria Giulini – Brahms: Violin Concerto (2015)

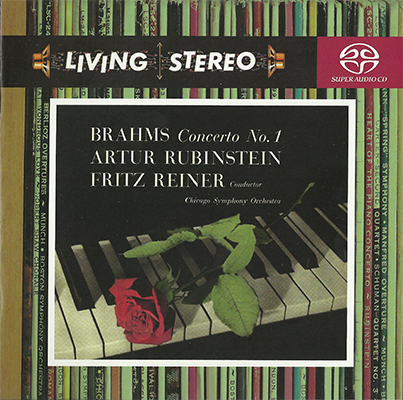

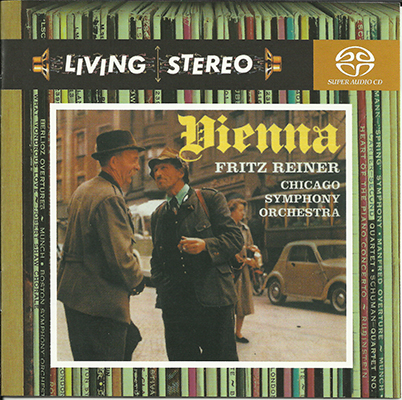

FLAC (tracks) 24 bit/96 kHz | Time – 43:11 minutes | 804 MB | Genre: Classical

Studio Masters, Official Digital Download | Digital Booklet, Front Cover | © Warner Classics

Brahms’s Opus 77 exemplifies the violin concerto of the Romantic era, just as Beethoven’s Opus 61 does that of the Classical age. As imposing as it is virtuosic, more than almost any other work in the genre, it leaves the soloist with nowhere to hide. For generations, it has been a work that any violinist aspiring to join the very select club of great masters of the instrument has had to conquer.

Countless recordings have been made of it now, throughout the twentieth century and continuing at the same pace into the twenty-first, proof positive of the enduring charm it exerts over both audiences and performers. It requires both romantic inspiration and technical expertise from the soloist; power, dynamism and a rich palette of colours from the orchestra; and real leadership from the conductor — and this complex alchemy has resulted in a number of legendary recordings. Since the pioneering versions set down by Fritz Kreisler in 1927 and Joseph Szigeti a year later, such luminaries as Jascha Heifetz, David Oistrakh, Nathan Milstein, Yehudi Menuhin, Ginette Neveu, Johanna Martzy, Leonid Kogan, Isaac Stern and Christian Ferras have joined the stars in this particular firmament. While there is a (probably pirate) live recording of Itzhak Perlman from 1968 (Intaglio), his first official version dates from 1976. This memorable album was also his first collaboration with the great Italian conductor Carlo Maria Giulini (1914–2005), with whom he was only to work in the studio once more — four years later, when they recorded the Beethoven concerto (see volume 28).

The prospect of following in the footsteps of Beethoven and Mendelssohn and writing a violin concerto was a daunting one, even for a composer of Brahms’s stature. Although there are undeniable affinities with the Beethoven work — the home key of D major, obviously, but also the respective proportions of the individual movements and the symphonic character of the work as a whole — Brahms met the challenge by establishing new criteria in the Romantic violin concerto tradition. He had worked closely with the concerto’s dedicatee, his close friend Joseph Joachim, asking him for technical advice on the solo part in order, as he wrote, “to avoid any clumsy figurations right from the start”. After some heated discussions, Joachim, who was a composer as well as a brilliant violinist, succeeded in obtaining the modifications he deemed desirable, and thereby the following drily humorous dedication: “You’ll think twice before asking me for another concerto! There is an excuse for the fact that this one bears your name, and that you are therefore at least partially responsible for the violin writing.” Although he had initially cast the work in four movements, in the end Brahms jettisoned the scherzo, a piece he is thought to have reworked later for his Second Piano Concerto.

The premiere, given by its two creators, on 1 January 1879, was quite well received, but the work was far from an instant success. French composers, led by Lalo and Fauré, were notably and almost unanimously in opposition, while Pablo de Saraste refused pointblank to perform it. “Do you think I have so little taste as to stand on the stage and listen, violin in hand, while the oboe plays the only tune in the whole work?” he is supposed to have exclaimed, alluding to the sublime first appearance of the central Adagio’s main theme. The fact that Sarasate and Lalo were good friends probably had something to do with the violinist’s rejection of the work, which was also a sly way of reproaching his great rival Joachim for having had a concerto tailor-made for him.

As with the Beethoven concerto, many virtuoso players wrote their own cadenza for the Brahms. Joachim, of course, supplied the first one (a remarkably sympathetic piece of writing), and his example was followed by two of his pupils, Hugo Heermann and Leopold Auer. They were soon joined by Ysaÿe, Ondrˇícˇek, Kneisel, Marteau, Kreisler, Kubelík, Busch, Heifetz, Milstein, Enescu and Ricci, while certain non-violinist composers also tried their hand, including Donald Tovey (1875–1940) and Ferruccio Busoni (1866–1924), the latter even marking his cadenza “with orchestral accompaniment”! The tradition has continued, with such current stars as Nigel Kennedy, Maxim Vengerov and Joshua Bell performing self-penned cadenzas on their recordings. Here, however, Itzhak Perlman goes back to the original, and plays Joachim’s — the ideal choice in many ways, not least because of its historical connections to the work. –Jean-Michel Molkhou

Tracklist:

01. Itzhak Perlman, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Carlo Maria Giulini – Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 77: I. Allegro non troppo (24:42)

02. Itzhak Perlman, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Carlo Maria Giulini – Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 77: II. Adagio (10:08)

03. Itzhak Perlman, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Carlo Maria Giulini – Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 77: III. Allegro giocoso, ma non troppo vivace (08:20)

Download:

![Philharmonia Orchestra, Carlo Maria Giulini – Mozart: Le Nozze di Figaro [2 SACDs] (1959/2021) SACD ISO](https://imghd.xyz/images/2024/05/08/d9845798f31051202e9e69176f4af936.jpg)

![Vladimir Ashkenazy, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Sir Georg Solti – Beethoven: Piano Concertos Nos. 1-5, Piano Sonata No. 29 Op. 106 (2020) [3x SACD] SACD ISO](https://imghd.xyz/images/2024/03/10/d01c3a53da81273665d8c309ba034029.jpg)

![Emil Gilels; Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Fritz Reiner – Tchaikovsky: Piano Concerto No.1, 1812 Overture (2014) [Official Digital Download 24bit/192kHz]](https://imghd.xyz/images/2023/10/14/k4Ivgio.jpg)

![Itzhak Perlman, Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy – Tchaikovsky: Violin Concerto; Sérénade mélancolique (2015) [Official Digital Download 24bit/96kHz]](https://imghd.xyz/images/2023/10/14/0825646073764_600.jpg)

![Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Seiji Ozawa – Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 5; Mussorgsky: A Night on Bare Mountain (1969/2017) [Official Digital Download 24bit/192kHz]](https://imghd.xyz/images/2023/10/14/0886446324104_600.jpg)

![Carlo Maria Giulini, Wiener Philharmoniker – Bruckner: Symphonie No.9 (1989) [Japan 2019] SACD ISO + DSF DSD64 + Hi-Res FLAC](https://imghd.xyz/images/2023/09/19/008a1fa5.jpg)

![Gaston Litaize, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Orchestre de Paris, Daniel Barenboim – Saint-Saens: Symphony No. 3 “Organ”; Bacchanale from “Samson et Dalila”; Prélude from “Le Déluge”; Danse macabre (1976/2013) [Official Digital Download 24bit/96kHz]](https://imghd.xyz/images/2023/08/28/0002894790559_600026d11a4c9e8660a.jpg)

![Peter Serkin, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Seiji Ozawa – Schoenberg: Piano Concerto, Op. 42; 5 Piano Pieces, Op. 23 & Phantasy, Op. 47 (1968/2017) [Official Digital Download 24bit/192kHz]](https://imghd.xyz/images/2023/08/30/0886446324081_600.jpg)

![Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Claudio Abbado – Mahler: Symphony No. 6 ‘Tragic’ (1980) [Official Digital Download 24bit/192kHz]](https://imghd.xyz/images/2023/06/09/whe5yf8o0xr2b_600.jpg)

![Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Claudio Abbado – Mahler: Symphony No. 5 (1981/2017) [Official Digital Download 24bit/192kHz]](https://imghd.xyz/images/2023/06/09/0002894798403_600.jpg)

![Carlo Maria Giulini, George Szell – Lucerne Festival Historic Performances Vol. VIII – Annie Fischer plays Schumann – Leon Fleisher plays Beethoven (2015) [Official Digital Download 24bit/48kHz]](https://imghd.xyz/images/2023/05/30/eyJidWNrZXQiOiJwcmVzdG8tY292ZXItaW1hZ2VzIiwia2V5IjoiODA3NzU4My4xLmpwZyIsImVkaXRzIjp7InJlc2l6ZSI6eyJ3aWR0aCI6OTAwfSwianBlZyI6eyJxdWFsaXR5Ijo2NX0sInRvRm9ybWF0IjoianBlZyJ9LCJ0aW1lc3RhbXAiOjE0NDUwMDI4MDR9.jpg)

![Los Angeles Philharmonic & Carlo Maria Giulini – Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 in E Flat, Op. 55 (2019) [Official Digital Download 24bit/96kHz]](https://imghd.xyz/images/2023/05/29/ur24jtmpmmebc_600.jpg)

![Los Angeles Philharmonic & Carlo Maria Giulini – Beethoven: Symphony No.6 in F, Op. 68 (2019) [Official Digital Download 24bit/96kHz]](https://imghd.xyz/images/2023/05/14/vauds6zv2j4qc_600.jpg)

![Jascha Heifetz, Fritz Reiner, Chicago Symphony Orchestra – Brahms: Violin Concerto (1955) [APO Remaster 2015] SACD ISO + Hi-Res FLAC](https://imghd.xyz/images/2023/04/13/ilQtLx3.jpg)

![Jacqueline Du Pre, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Daniel Barenboim – Dvorak: Cello Concerto & Silent Woods (1971) [Japan 2011] SACD ISO + Hi-Res FLAC](https://imghd.xyz/images/2023/04/10/qoQu8Jl.jpg)

![Claudio Arrau, Philharmonia Orchestra, Carlo Maria Giulini – Brahms: Piano Concertos Nos. 1 & 2 (2023) [Official Digital Download 24bit/192kHz]](https://imghd.xyz/images/2023/04/02/zru40zyc0qt8b_600.jpg)

![Itzhak Perlman, André Previn – Joplin: The Easy Winners & Other Rags (2015) [Official Digital Download 24bit/96kHz]](https://imghd.xyz/images/2023/03/30/0825646073948_600.jpg)

![Itzhak Perlman, Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, John Williams – Cinema Serenade (1997) [Reissue 2015] SACD ISO + Hi-Res FLAC](https://imghd.xyz/images/2023/03/23/rTbYhfH.jpg)

![Itzhak Perlman, Cantor Yitzchak Meir Helfgot – Eternal Echoes: Songs and Dances for the Soul (2012) [Official Digital Download 24bit/44,1kHz]](https://imghd.xyz/images/2023/03/18/0886443560505_600.jpg)

![Itzhak Perlman – The Complete Warner Recordings 1972 -1980 (2015) [Official Digital Download 24bit/96kHz]](https://imghd.xyz/images/2023/03/18/IpmBmeR.jpg)

![Itzhak Perlman, Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, André Previn – Goldmark: Violin Concerto No.1; Sarasate: Zigeunerweisen (2015) [Official Digital Download 24bit/96kHz]](https://imghd.xyz/images/2023/02/11/0825646072736_600.jpg)

![Itzhak Perlman, Emanuel Ax – Fauré & Strauss Violin Sonatas (2015) [Official Digital Download 24bit/44,1kHz]](https://imghd.xyz/images/2023/01/30/0002894811882_600.jpg)